This tongue-in-cheek piece was written by OG Michael Kielstra, a current Mathematics student at Harvard University.

Estimated read time: 4 minutes

Every so often, some wag will restart the debate over what is and what isn’t a “useful” degree. This might be someone on the internet, or it might be your father asking why he’s paying all this money for you to do East Asian Studies or Theater and Dance or Classics while your older brother studied Computer Science and now he’s pulling down £80 000 per year with benefits. Academics often weigh in to defend their own fields, often using phrases such as “[The thing I study] has never been more relevant than today”. The main divide seems to be between, on the one hand, the group that views education as job training and a college degree as an investment to be netted out against future earnings, and, on the other, the group that views education as teaching knowledge and good citizenship for their own sakes. I call these groups the plutophiles and sophophiles respectively. The sophophiles view the plutophiles as short-sighted money-grubbers with no sense of beauty, while the plutophiles view the sophophiles as pie-in-the-sky idealists with no sense of pragmatism.

The divide between these two groups is very easy to see on a college campus. Arts and humanities majors tend to be sophophiles, resigned to the fact that they will never earn as much as the people in the science building and making highfalutin arguments about how that doesn’t matter. Science and engineering majors, on the other hand, are more often plutophiles, angling for high-paying jobs in the financial or technological sectors. As we will see, there is more nuance to it than that, but this, I would say, matches up fairly well with most peoples’ first impressions.

At this point I should introduce myself. My name is Michael Kielstra and I am a math student at Harvard. This should immediately put me on the list of plutophiles, or at least on the list of people with degrees that their grandfather isn’t ostentatiously ashamed to talk about. Ever since theology was dethroned, mathematics has been the queen of the sciences, and, knowing the job opportunities for engineers, we can only imagine those open to mathematicians.

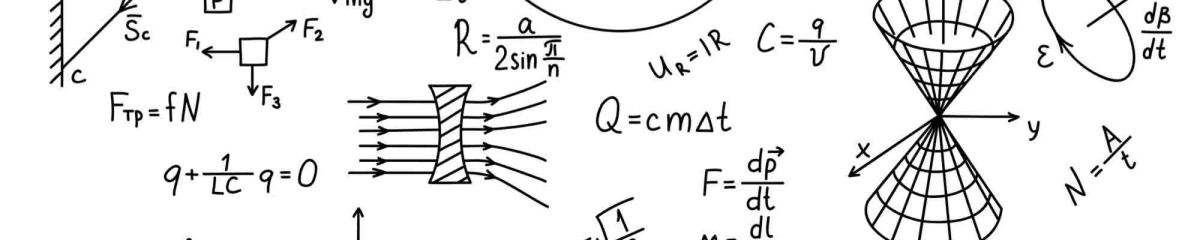

However, a math degree, from a plutophilic standpoint, doesn’t actually make very much sense. As anyone who has heard mathematicians talk will know, mathematics very quickly becomes abstract and abstruse. Only this year, I have done problem sets involving hierarchies of infinite numbers, derivatives in curved high-dimensional space, and symmetries of arbitrarily complex shapes. More importantly, the engineers don’t need much of this. I am currently enrolled in a class on high-performance computing, and my fellow-students are struggling with algebra which, to me, is almost trivial. I’m not trying to brag here: it is in fact I who am the stupid one, plutophilically, spending all this time practicing algebra that our brightest high-performance computing experts can mostly get by without. Engineers and computer scientists know a lot of mathematics, certainly, but much less than mathematicians do. They fill up that space in their heads, instead, with practical knowledge that equips them to make money in the real world. The plutophile laughs at mathematicians.

This would explain why so many mathematics professors are sophophiles, regularly publishing tracts eulogizing the beauty of their “independent world/created out of pure intelligence.” (Even Keats got in on this.) That doesn’t make much sense either. I can, and often do, rhapsodize with the best of them about the wonder of high-level mathematics, but it is a wonder denied pretty much entirely to people who aren’t willing to spend hours and hours and hours working on problems that seem hopelessly

convoluted and nigh-on incomprehensible even to professionals. Mathematics has a very high person-hours-to-beauty ratio. On top of that, once the modern professional mathematician does create something beautiful, there are possibly ten thousand people in the world who can immediately appreciate it, and possibly one hundred who can appreciate it fully in context.

And mathematics provides next to no training in citizenship, leadership, or any of the ineffable qualities that sophophiles so regularly argue can be taught at university. Mathematicians are famously absent-minded and socially unaware. Imperial College, in the second year of their mathematics degree, brings in a drama coach – not an executive coach or an education expert, a drama coach – to teach the students how to give engaging presentations. The culture of pure mathematics, although in many ways wonderful, has a tendency towards detachment, arrogance, and the worst kind of agnosticism. The existence or non-existence of God does not follow from the Morse-Kelley axioms of set theory, so why should we care? Why should we care about people who care?

So if mathematics makes no sense to a sophophile, and it makes no sense to a plutophile, we may draw one of two conclusions from the fact that I’m still doing it. The first is that I am thick. I am going to ignore that possibility. The alternative is that the distinction between plutophiles and sophophiles is incomplete at best. This is strange: express any even mildly controversial opinion about higher education, and you will very easily find someone ready to call you a dirty sophophile or a filthy plutophile. However, I believe that grouping our opponents, and thereby ourselves, into these categories is a major mistake. After all, neither category can explain a degree as popular as mathematics. The sophophiles and plutophiles, locked in combat over the purpose of higher education, have so limited their viewpoint that they cannot understand that there might be subjects and courses without a fixed purpose at all.

This is the fundamental error: viewing education as a means to an end, whether that end is to produce billionaires or to produce, to borrow a phrase I loathe from the official mission of Harvard College, citizens and citizen-leaders. Talking about whether something is a “useless” degree presupposes that “use” is an adjective that should always apply to degrees in the first place. The mathematics degree is best explained not as a means to an end, but as an end in itself. I love to do mathematics, I love to learn mathematics, and, yes, deep down, I even love the feeling of working on a really nasty problem set. I love the subject, I personally find it beautiful even if I know that beauty is very esoteric, and I would find a life full of it to be fulfilling. That is all the defense I can give for my life choices, and I believe it makes me an incurable Romantic that I believe it is all the defense I need.

A college degree, in any subject, with any sort of usefulness, is just another option that may not be right for everyone. If you want to create beauty, be an artist. If you want to be a citizen-leader, volunteer. If you want to do what you love, and the thing you love happens to be something for which a college offers a degree, go to college. I want to do math, and I am privileged enough to be able to afford to use a facility designed to help me to do math, so I make use of that facility.

If you want to make money, honestly, I’d recommend plumbing.